Sep 2019

Think Piece: Military and Police: Mission Interoperability By Peter Watt

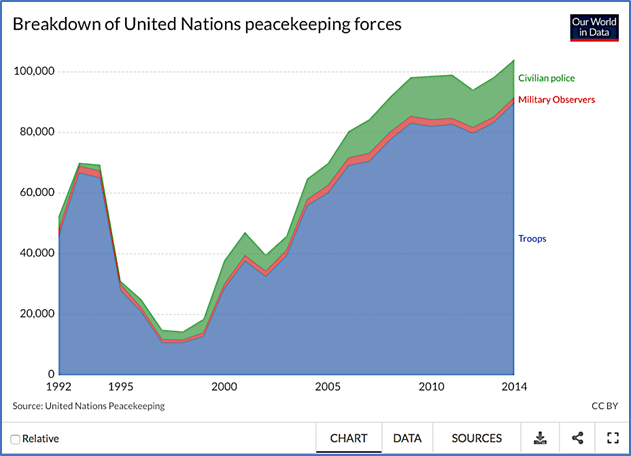

Although police numbers in UN peacekeeping are fewer in comparison to military troops, both play key roles in peacekeeping and work together to achieve the goals of their own government and the UN mandate.

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) leads the UN police deployments in Australia, seconding state police as required. 60 Australian police personnel were selected to be part of the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET) in 1999. Prior to deployment, police were trained by Australian Defence Force personnel in Canberra.

I served with the AFP as a CIVPOL Senior Sergeant for 28 years and was stationed in the Ermera region of Timor-Leste with a number of International Military Liaison Officers (MLO’s) including Australian MLO Captain Dan Grogan, one of 50 MLO’s posted to Dili and the 13 districts under the UNAMET mandate.

The MLO’s main role was to liaise between the Indonesian National Military (TNI) and the East Timor Falintil (Freedom fighters). Police peacekeepers were to provide advice to Indonesian police (Brimob and Polri) and monitor the registration of Timorese voters in the lead up to and on the day of voting that took place on the 30th August 1999.

Grogan and I both arrived in the town of Gleno, Ermera just days before voting day. Along with others on the ground, we experienced a series of violent attacks by armed and drug-induced militia. On the day of the referendum results announcement, US police peacekeeper Earl Chandler was shot. I was evacuated from Dili to Darwin September 15, along with the last of the unarmed UNAMET police peacekeepers. In total, 271 unarmed police were deployed to UNAMET from 27 countries. Due to increased militia threats, all UN personnel were evacuated 11 days after the announcement of the referendum results.

Five days later, the International Force East Timor (INTERFET) peacemaking taskforce arrived to address the humanitarian and security crisis that took place in East Timor from 1999–2000.

During the 1999 UNAMET Popular Consultation, Australian CIVPOL Commander Geoff Hazel, a former member of the 3rd Battalion Royal Australian Regiment in South Vietnam and Australian Army Training Team Advisor, spoke about Australian MLO’s and CIVPOL’s working relationships in UN missions:

“The UNAMET mission had a number of components including Military Liaison Officers and Civilian Police. Each component had its own role but co-operation from the other components was crucial. An excellent working relationship developed very quickly between the police and the military.

My prior military service knowledge of how the military worked assisted me greatly in my role in my day to day police work. The planning experience I had gained in the military as an adviser to South Vietnamese and Mozambique military units was also of great benefit in meeting some challenging situations. In both Mozambique and East Timor, I used knowledge from that experience to establish relationships with the MLO’s to achieve results with the local police organisations.”

In November 2000, I returned to Suai, Timor-Leste for the UNTAET mission in the role of CIVPOL Liaison Officer between CIVPOL and the Peacekeeping Force (PKF), under the Command of Brigadier Ken Gillespie in the UN Sector West PKF Headquarters in Suai.

The Australian and New Zealand Battalions were the major PKF units serving in Suai. They provided crucial support as requested to CIVPOL where civil conflicts occurred, which was the responsibility of CIVPOL. This included assistance in law and order issues, and disputes from incidents resulting from the movement and arrival of returnees from West Timor.

As CIVPOL Liaison Officer, I received key support from the PKF to set up the Police Operations Command (POC) for the Timor Police Service. Part of my role was to provide CIVPOL input into the PKF weekly briefings on security related matters that may impact the UNTAET Mandate. This required close working relationships between the two organisations.

I returned to Timor between 2016-2018 as a volunteer to work with a local training organisation that delivered training to the Timorese police and military in topics covering Information Technology, Train the Trainer, and Leadership.

Watt’s biography, Scorched Earth, written by former Australian Federal Police member Tammy Pemper, has recently been published by renowned international military publisher Big Sky Publishing. Together with the author, Watt is currently working with Veterans Care Association, including Timor Awakening, to help promote the book. Many who served in missions overseas are finding that the book helps them to tell their own stories, as difficult experiences are often hard to explain or talk about. There are also future plans to direct proceeds of the book to support PTS and mental health issues suffered by police and military peacekeepers.

****

Scorched Earth is supported by many testimonials including Australian film-maker Gil Scrine, who writes:

“History tells us that the UN supervised vote in East Timor was a betrayal of those who took part in it. The UN Peacekeepers, volunteers and others depicted in this heart-stopping account, went unarmed believing the Indonesian police and army were there to protect them. Yet, against all odds the UN pulled off a credible vote in which the Timorese chose independence…The heroism and raw honesty with which their story is told in SCORCHED EARTH, is a tribute not only to those brave UN volunteers, journalists and others but to the East Timorese themselves.”

Scorched Earth is available in paperback and e-book. Visit www.tammypemper.com to find out where you can purchase the book and to see where all profits are being directed.

“As a UN peacekeeper, I joined the East Timorese fight for life. By then, the earth had drunk the blood of one third of their population. But worse was still to come.

I would see it for myself.

I saw bodies carried to their deaths, machetes carve flesh from bone, and bullets spray into crowds of Timorese and at us peacekeepers. I learned the true meaning of fear, hopelessness, and courage. Shades of truth were twisted for evil gain. Every day I prepared to die. Decisions I made, which seemed so right, jeopardized the lives of others.

Police held automatic weapons to my head, militia wrote my name on death lists, and people drew their last breath, all of them brave, braver than me.

For this is the true story of my experience. In the midst of the East Timorese fight for independence, militia were determined to enact their scorched earth policy and raze Timor to the ground.”

Peter Watt, Scorched Earth